This Love Story Of Andrew And Doreen Augustus: Interracial Couple Married For Almost 60 Years Is Everything

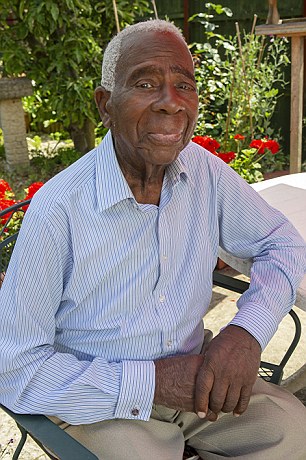

There’s nothing like a true love story; it captivates in no small measure. Right until she drew her last breath, Andrew Augustus’s love for Doreen, 87, his wife of almost 60 years, was unbreakable. He made her a promise when they first met: “If you don’t let me down, I’ll never let you down” and neither of them ever did. They were faithful to each other in a most constant and devoted manner until a day in June, 2017; when Doreen died.

What made their love story exceptional was the fact that they were a British mixed race couple — she, a white girl from Godstone, Surrey, and he, a West Indian immigrant from Dominica; such matches were almost unheard of in their time.

Their amazing story was told on “24 Hours In A&E” in which the couple was showed in an emotion-laden last moments together.

Though they faced racial prejudice, discrimination and the disapprobation of her family — and although both their communities spurned them in the early years of their relationship — their love for each other prevailed.

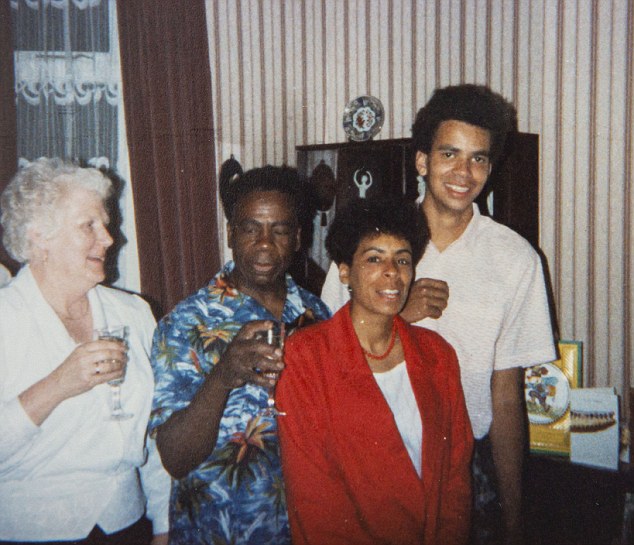

Andrew and Doreen raised two children, Penny, now 60, and Chris, 52, and sent them both to private schools. They overcame intolerance and bigotry, worked tirelessly and, against all odds, bought their own home in London. Andrew, who is now 86, still lives there with Chris.

And as Doreen’s health declined- she first suffered heart problems, then dementia- Andrew made his wife another pledge.

‘I said she would never have to go into a home, that I’d always look after her here. And I kept that promise, too.’

He remembers the morning she died at 87.

‘I’d given her her tablets and a cup of tea,’ he says. ‘She drank that. Then I started to feed her Weetabix. She ate four spoonfuls but wouldn’t take the fifth.

‘She opened her eyes wide and looked at me. Then she closed them and she was gone. I called to Chris, “Mummy’s gone”, and that was that.

‘I can’t forget how she looked at me — with such love. She couldn’t talk much then. She couldn’t finish a sentence.

‘I told her I loved her. She was a wonderful wife and I miss her terribly. She’s in Heaven somewhere. I gave her my love. I gave her all I had.’

A less committed couple would have been broken by the intolerance and injustice they encountered, but their devotion to each other never wavered.

They met just weeks after Andrew, one of the Windrush generation of early migrants from the Caribbean, arrived in London in February 1956. It was an era when landlords displayed signs in their windows decreeing, ‘No Blacks, No Irish, No dogs’.

Andrew secured a job at Selfridges in Central London, working seven days a week ferrying goods in the service lift and doing odd jobs. In Dominica, he had been a skilled carpenter, but in Britain; he had to take whatever work and accommodation he could find. He recalls:

‘I earned £5 a week and they took advantage of us really. I had to pay £2 a week for a bed in a house in North Kensington (near where Grenfell Tower would later be built) with eight others.’

At work, Doreen soon caught his eye. Slender and fine-boned, with beautiful wavy golden hair, she worked in the fur department, measuring rich customers for custom-made coats.

‘She looked like a model with this lovely hair,’ he says. ‘We started chatting and I used to ferry her up to the roof in the lift in our breaktimes. We’d go up there to have a smoke.

‘She said: “Why do you keep giving me lifts?” — and I said: “I love you. That’s why.” And I was lucky because she said she loved me back.

‘We did our courting on the roof at Selfridges. And we were faithful to each other always after that.

‘At dinner time, we’d go to Grosvenor Park behind the store and lie on the grass.

‘People would see us having a kiss and a cuddle and they’d point and stare and say: “Look, look! They’re kissing!” They’d just watch us because you never saw a mixed race couple together then.

‘Soon I asked Doreen to come for a meal at my place. I made rice, red beans and I bought a chicken. Doreen said: “What? Rice? That’s for pudding!” But I said: “No, that’s what we’re going to eat for our dinner.”’ He laughs at the memory: a low, rich, rumbling laugh. ‘And after that moment we never parted.’

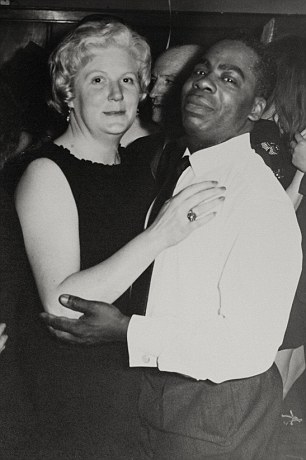

There were few places that they could socialize without stares, but they found a club patronized by students, where skiffle singer, Lonnie Donegan used to perform, and they danced there.

The path ahead, however, was strewn with obstacles. Within six months, Doreen discovered she was pregnant. They had to find accommodation that would accept them — a mixed race couple and an illegitimate child — in an age when the combination was an awful double stigma.

Finally they found a place in Kilburn, north-west London, in the home of an elderly woman who was prepared to let them a spare room.

Meanwhile, Doreen’s family, who did not even know she was seeing Andrew, let alone was about to give birth, had to be told. And there was a huge furore after that.

‘They reacted very badly,’ says Andrew with understatement. ‘Her elder sister said: “You can just give the baby away. Pretend it never happened.”

‘We didn’t tell her mum until after Penny was born, and it was chaos. Before she’d started courting, Doreen’s mother, who was then in service, had to ask permission from her mistress just to go out with her boyfriend. She was furious that Doreen hadn’t told her we were going out together — and even angrier about the pregnancy.

‘She wanted us to have Penny adopted, too, and we said, “Not on your Nelly!” ’

However, weeks after the birth, when Doreen’s parents finally met Andrew — and realized that he was not only loyal, dependable and hard-working, but also that he knew how to cook and launder clothes — their attitude changed.

‘Her mum came down expecting to help, but I was washing the clothes and making meals — I come from a big family so I knew what to do — and she softened.

‘She stayed three days and next time she brought her husband (a bus driver) too.’

Now, it is hard to imagine the privations they endured. They relied on the goodwill of their landlady so their accommodation, which was cramped, was also perilous. They could be asked to leave at any time.

And although Doreen had been highly valued by her employers (in fact she had been singled out for management training), she could not work once Penny was born because childminders were loath to look after mixed-race children.

The solution was for Andrew to work even harder. He went to night school and got the formal qualifications which allowed him to work as a skilled carpenter on building sites.

Meanwhile, he and Doreen were determined that their daughter should have the best they could afford. They bought her a carriage-built Silver Cross pram — the very model the Queen had for the Royal babies — from Selfridges. (As former employees they were given a generous discount.)

‘We used to take it on the Underground and people would stare and say, “We’ve never seen a pram like that on the Underground!”’ marvels Andrew.

Doreen, meanwhile, kept house and looked after Penny, pushing her to Lord’s cricket ground to watch the afternoon’s play.

The couple were married at Willesden Register Office in August 1961, and moved into a house in Streatham, owned by relatives, where they rented rooms.

As space was tight, they agreed not to have another child until they had found permanent accommodation of their own. The sacrifice was a difficult one for them, and it accounts for the eight-year age gap between Penny and Chris. They remained oddities in their predominantly white neighbourhood, and were ostracized by many people.

Neither did Andrew’s community accept them. He remembers:

‘A lot of them dropped me. In those days, some white women made themselves available to black men, but they weren’t the sort of girls who’d marry them. So there was a bit of jealousy.’

Andrew had by now become a foreman, and thanks to his diligence and the couple’s thrift, they were able to send Penny to private school. Meanwhile, they had also saved enough for a deposit on their own home.

In the mid-Sixties, they paid £4,540 for the Victorian terrace in which Andrew still lives. Their path was free for Doreen to have another child and in 1966, to their delight, Chris was born.

He, too, went to private school, and although money was at times tight, the fees never went unpaid because Andrew took all the overtime he was offered to meet the responsibilities.

However, the social acceptance they’d hoped for still eluded them. Even in the Seventies, racial intolerance was rife.

Chris recalls the day the family planned a boat trip on the Thames.

‘There was a bit of a scene and Dad got into a row because the captain wasn’t too happy they were a mixed race couple. Apparently, one or two passengers had complained and wanted us to leave.

‘Dad wouldn’t put up with that kind of nonsense. He said, “Stuff your boat. We’ll go somewhere else.”

‘It wasn’t so long ago, but in terms of attitude it was a different era. But Mum never let people see that she was upset. They stuck together through good and bad times. They were so happy.’

Doreen, says her son, was ‘proud, strong-minded and loving — the hub of the family’.

And as her children grew older, she started to work again, getting up at 4 am to clean offices, then working at the passport office in Petty France, Central London, once they were grown up.

Andrew had progressed in his job, too, and was building film sets at Pinewood Studios in Elstree for such films as Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, the Battle of Britain and the Carry-Ons.

In their own quiet way, Andrew and Doreen were pioneers — advocates for racial equality before the term had even been coined.

They were hard-working, morally upstanding members of a community that — at least in the early decades of their marriage — treated them with contempt. Yet they stood together, their love firmer than ever, against the bigots.

They were exemplars, too, of how good marriages work, for Andrew cared for Doreen in sickness and in health. She was 74 when she started to become unwell and had an operation for a heart murmur.

‘She was scared, I was scared, but I never showed it,’ Andrew recalls. But the operation signalled a permanent decline in Doreen. Her memory started to fail — it was the first sign of dementia — and the joy seemed to have been sucked out of her.

‘Mum used to be vigorous and strong, and to see her so weak and poorly and unable to care for herself was upsetting,’ says Chris, who now helps care for Andrew.

‘But Dad was very protective of her. He took charge. He was absolutely determined to look after her.’

And so he did, until she died in June, 2017. During Doreen’s final illness, he was with her, stroking her hair and soothing her; his large, capable hand cradling her tiny, delicate one.

Their story, as told on TV is a touching one. We see Andrew at Doreen’s side as she is admitted to hospital with sepsis. She rallies after she is given intravenous antibiotics and four days later was discharged. But within three months, Doreen died in their home.

Today no one, of course, would be shocked by Doreen and Andrew’s mixed race marriage. The hospital staff — black, white, Asian and Eastern European — cared for her with the mix of professionalism and kindness that she was due.

Above all, Andrew was with her, protective, tender and loving — as he promised her he would be — right to the last.

Culled from Dailymail