Mothers Of Autistic Children Share Their Agonizing Experiences As They Create Awareness About The Disorder

For Solape Azazi, author and producer, taking care of her autistic son whose health condition was discovered months after birth has been an unexpected challenge.

Her pain runs through the narrative as she still recalls that the boy-child developed when he was supposed to develop, walked when he should walk, and talked when he should talk and everything else.

At 12 months he was saying the words that one would expect a 10, 12 months old baby to be saying. At 15 months, things started changing in his life. He still had the words but didn’t have more words. At 18 months, he had fewer words; then at 20 months he had no words.

“So by the time he started talking again, a child that was already saying, mummy come, daddy come, suddenly went to baby babbles. By the time the doctor assessed him, he said that the baby had regressive autism, and had lost all the skills,”

Azazi told Daily Sun.

As a mother, Azazi went through emotions as soon as she discovered that. She asked herself many unanswered questions. She continued:

“We couldn’t understand why, or what was going on. Being a young bride, having a first child, not knowing what to do, I began to blame myself.”

What next? She went into depression because she couldn’t believe and understand it. However, she regained composure, having realising that it was not her fault. She had to face the challenge because the child was growing.

Azazi came to terms with the fact that the boy needed her support; and stood up to the challenge so that he could grow and thrive regardless of his setback.

Challenged by her son’s health condition, Azazi has been unrelenting in not just sharing her experience, but also in creating awareness about autism.

“I have written a children’s book to teach children about autism. I have done a documentary on navigating autism in Nigeria. I go into the communities to talk to parents about autism in Nigeria. I have partnered with Obalande Local Council Development Authority (LCDA) to try to build awareness within Obalende. I talk to parents who have children with autism.

“I still cry, because at times, there are things you would wish and dream up for your child and you see that your child cannot be there. It breaks your heart. Things like that would make you cry, but then you remember again that in all of these, the child is doing his best that he can within his capability.

So all you can do is to support that child. Give that child the opportunity to fly and you would be amazed. My son draws so well. He paints spectacularly. So imagine if I don’t allow him to thrive in that area, insisting that he does something else. I would fail to be the parent that he needs for himself.”

Now armed with a wealth of experience in handling her own child, Azazi finds herself advising mothers who have autistic children. She said:

“I will never say don’t cry, but when you finish, wipe yourself and pick yourself up and stand up, because there are times that it can be a lot. For me it was a lot.

Sometimes I even say to myself, can I handle it? But then I remember that I am a Christian and God has not given me the spirit of fear, and that He gave me this child for a reason.

So as a parent I would advise that, so long as you have the right support; people to lift you up when you are down, rise up, and you would be surprised that you have people that would support you. That child can do a lot if you believe in that child.”

She believes that the government can do a lot to support by providing access and creating awareness.

“Let people understand, be aware, and bring their children out. Let people be included in policy making. Include our children also in policies that are effective,”

Azazi said, having realized that in autism there is no cause, no cure, “just a different way of life.” But she is not alone in this.

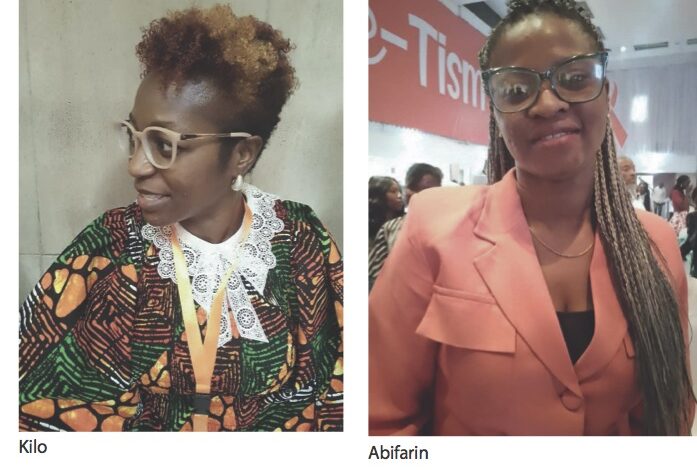

Bode Abifarin is another woman who has done a lot in supporting her nine-year-old twin boys with autism on their journey.

In the quest to give them a better life, she went back to school to do some courses on autism. As a result, Abifarin has completed several short courses in speech therapy, behaviour modification, and behaviour analysis.

She also went into writing books on autism to make it easier for parents who have autistic children to learn how to handle them.

Her book, ‘The Boy with a Happy Feet Dance’ was written to show that there are endless possibilities in autism as long as one has patience and the consistency in terms of the gifts-fanning their gifts and passion. From her experience, it is, sometimes, difficult to find out the gift of that child.

“I just threw a lot of things at them such as swimming, basketball, cycling. I found out that over time in the beginning, it was difficult. Even for practices when you think nothing would happen, just go there, be consistent,”

she noted. She admonishes parents not to be weary. She said:

“Even when you are, tap into your strength and community, keep up with the practices. It took one of my sons almost seven months of nothing in practice, but he was taking everything in, while his other brother was already swimming, until one day we put him in the water and he started gliding. Now he would be the one to say that he wants to go swimming.”

What more should distraught parents do? She added:

“Simply get a diagnosis. Don’t be afraid. There are a lot of resources online. With programmes like that of GTCO now, you can go and find out what people have done, find out about the centre, go there, sit down, make inquiries, ask questions, go back, cry, dry your tears, but chart a path forward.

In the community, get help as much as possible. Don’t hide yourself from the family that would help you, so you can rest a bit. As you learn, also be a light to someone. One of the things that set me free is beginning to understand the communication of the child. I use pictures and prints for life.”

Ten years old Michael Odukoya has been autistic from birth. His mother, Olajumoke Salami narrated her experience:

“When I gave birth to him, he did not respond. We passed his food and drugs through a straw. The midwife suggested that they should throw him away because he was not breathing well, but I refused since he was still breathing. By the third day, he turned green.

As we were preparing to take him to the general hospital, he sneezed. Even though they were birthing him with hot water, he wouldn’t cry. When they finished birthing him, they would put him in the morning sun and take him inside after the morning sun. He opened his eyes after eight days during his naming ceremony.”

Salami was later abandoned with the child by her husband and his family members. To ensure that Salami never had access to them, the husband and his mother relocated to a location that is still unknown to the wife.

“I don’t have contact with any of them. It was only me and my family that were taking care of him. He attends school at Dopemu, Akowonjo in Lagos with the help of my family members. It has been stressful for me.”

Even though Salami has started a new married life, she still lives with the burden of caring for her autistic child.

“I can’t work because of him. I can’t leave him with anybody, so I go with him everywhere because no one can cope with him. He does not chew. When he wants to eat something like beans, I use to mash it. I cannot cook yam because he can’t eat it. Even very soft food he can’t eat at times. That is why no one else can stay with him except me,”

she lamented.

Way forward for Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

At the just concluded autism conference organised by Guaranty Trust Holding Company (GTCO), in Lagos, some of the resource persons who have children and family members with autism, shared their experiences.

The event with the theme, ‘A Spectrum of Possibilities,’ simply means that there is no limitation to what an autistic child would do.

Segun Agbaje, MD/CEO, GTCO, said that the bank has raised awareness, fostered understanding, and championed the rights of individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). He said:

“Each step we have taken is proof of our commitment, and the incredible impact we can achieve when we unite for a common cause. When we talk about autism, it is with great passion and responsibility, one that we as advocates, caregivers, researchers, and supporters, embark on side by side with individuals on the spectrum.”

He referred to the theme of the conference as fitting, saying that it emphasised the bank’s commitment to shining a light on the experiences, challenges, and strength of individuals with autism and encourages a culture, acceptance and inclusion for not only individuals with autism, but also their families and caregivers, which in turn removes stigma, thus reshaping the conversation about autism.

Nadia Hamilton, a passionate entrepreneur who was inspired by her autistic brother to build Magnus Cards, an innovative App that provides digital, step by step visual guides.

The App is in the form of collectible card decks, to support home and community living for autistic and neuro divergent people worldwide.

“I had to find out who is really helpful for my brother. I get his attention and make it amazing. I support my parents when I can.”

Hamilton said her brother, Troy, plays piano, and joins his dad in his construction work.

For Camille Proctor, an advocate, dedicated mother and a driving force behind autism awareness and inclusion initiatives, her journey into advocacy began in 2008 when her now 18 year-old-son was diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder shortly after he turned two.

She noted that some of them have special interests and that is the only way they can work for themselves. Her son cooks, and bakes with his mum.

She advised parents to give them the opportunity to participate in what they love to do.

“Don’t be afraid to say what you need for your child. Show them love and give them a strong foundation. Don’t ever take them for granted,”

Proctor advised.

For Remi Olutimayin, an autistic adult, and one of the resource persons at the event, his condition is not a limitation. He is a voice director, actor, and producer. He is the first African voice actor to be internationally ranked in animation on the continent by the Society of Voice Arts and Science (SOVAS).

Olutimayin has over two decade’s work experience in animation, audio books, e-learning and documentaries. His projects include multiple award winning animation, ‘Ajaka, Lost in Rome’ and ‘Our Own Area Animated Series’.

His word of advice on spectrum disorder is,

“Express yourself clearly. Identify your friends. I followed my curiosities as an abstract thinker. Find out how it works in the world if you are going to be independent. Follow your curiosity.”

A major source of concern is how to integrate children with autism into the society.

Oluwatomi Agboola Odeleye, a Legal Speech and Language Therapist at multi-disciplinary practice in London, in his presentation, noted that autism is something that affects 10 per cent of the population. That means out of 100 children, 10 are qualified for diagnosis of autism.

“If you are testing them genetically, there is a genetic problem that they all have. So there is something biological, neurotically, that happens at the very early years, which changes their brain’s function and process.”

To integrate them into the society, Odeleye recommends that the first step is to give them a voice.

“Depending on whichever level they are, even if they are non verbal and have no voice, use something like a communication board, iPad, symbols and visuals to let them know, say what they need, want and to be able to ask questions.

The ones that are higher and more functioning look for opportunities for them to work. Many of them can go to school, so that when it comes to finding employment, they could live on and be independent.”

Lanre Duyile, President/CEO, Behaviorprise Consulting, noted that rather than see disabilities, there is a need to see possibilities with the folks with autistic spectrum.

Duyile who is also the proprietor of Behaviorprise College of Business and Health Studies, Toronto, Canada said:

“A lot of times when we think about their mental disabilities and new divergence, people think about limitations, that they are not able to do anything.

But beyond that, the individuals that we work with can actually do more. They give us insight into what is going on with them, with us and what the outlook that they have about the world is like. So it is just beyond limitations.”

Still on the strength of an autistic child, Bernadette N. Kilo, a Cameroonian medical doctor, who has three autistic children (Two boys and a girl) noted that the most common aspect that a lot of parents are quick to notice is lack of speech and language acquisition.

“Verbal expression only makes up 14 per cent of communication. The rest 86 percent of communication is non verbal, it is gesture. A lot of times we pay attention to only 14 percent which is the expressive language.

We need to learn to pay attention and use all our senses to effectively communicate. Autism uses a lot of gesture, sensory behaviour to communicate. These three things make up 86 percent of what we don’t use. That is one of the strengths of autism. The other ones they are quick to recognise are patterns.”

She explained that autistic children are hyperactive when they cannot communicate very well. She further counselled:

“Medical school did not teach me, but three people who taught me are the very children in my own house. My first son, we call him Bit boy, gave me my PhD in autism.

My second son, called the mathematician, taught me that autism has another face, and my third child, the jewel, the girl, showed me what autism in a girl looks like. We call her the headmistress.”

She expressed dismay over the stigmatisation of children with autism, and blamed the society for it.

“If we learn to define autism from its strength rather than its challenges, we remove stigma and fear. Once we do that we begin to speak the language of identifying strength first. So what we must do as a people and as a community is to learn the pluses that autism has.”

One of the first steps parents must take, she says, is take the child to a paediatrician depending on what area of challenge the baby has.

“There is something like speech therapy in helping the child. If the child has not acquired speech and language, then start with that. Also help the child with communication because speech and language is just one aspect of communication.”

Eniola Lahanmi, a speech and language therapist with over a decade of experience working with children with autism and developmental challenges, reiterated that with autism, there is no sort of limit to what they can achieve.

Rather all they need is support from the society to do those things that they can do very well, and to know that with the right support the sky is their limit.

She applauded the country for being able to give them a sense of belonging saying,

“For us, we have come a long way. In the past decade you would see that we had a lot of people who didn’t know what autism was, but in recent times, we have seen a lot of awareness, education in terms of what it is and getting a message out there.”

Caregiver’s experience

Quadri Fatima Bolanle is the Programme Coordinator and Director of a special needs school, Heart and Soul Centre, for children with special needs in Ibadan, Oyo State. She explained some of the challenges faced by caregivers of autistic children.

“We face a lot of challenges taking care of these children, such as getting the necessary resource materials. We have financial challenges too, because most of the parents with these kinds of children are not ready to finance their education.

Some of them who have the money prefer to spend the money elsewhere, instead of focusing on these children. So we use a lot of our own personal resources to take care of them, and it’s not easy.

Also, sometimes their health needs are more than their educational needs. We have to spend a lot in the hospital taking care of their medical needs.”

Bolanle has her share of frustration in handling autistic children.

“You do it consistently hoping that things will improve. Sometimes, they relapse and it gives you a lot of trauma, but as trained caregivers we don’t lose hope on them, hoping that one day the children would evolve and respond better to therapies,”

she lamented.